Last time I examined how God eats us — taking us into his body. “Abide in me as I abide in you.”

He eats us by having us eat him: by consuming his word.

The model for this is given in Joshua, who of course is a shadow of Christ: In order to overcome the nations of the promised land, as Christ overcomes the nations of world in us, God tells Joshua, “the scroll of this law shallt not depart out of thy mouth, and thou shalt murmur in it by day and night.”

In the next verse, God connects both Joshua’s having the word in his mouth and having good success, with having God himself with him: “for Yahweh thy God is with thee in all places that thou goest.”

It is obviously striking to compare these words with what David says about the blessed man in Psalm 1:

in his law he murmureth by day and night…and all that he doeth shall prosper. (vv 2–3).

David also links this murmuring to the spiritual pattern of eating, of consumption, going back to Eden and comparing the man who delights in God’s law to a tree planted upon waters. The tree takes up the water of the word, and from it he produces fruit. David in fact is being very “meta,” because his psalm is itself an example of this very process. Transformation and glorification are central to the idea of consumption: the tree takes up the dirt and glorifies it by transforming it into fruit. Adam eats the fruit and glorifies it by transforming it into his own body, which is the image of God. And God integrates Adam into his own body, glorifying him by transforming him from glory to glory — ultimately, of course, achieved through Christ, where God fills the human nature with his own fullness, in order that humans may partake in the divine nature.

In the same way, David takes in the law of God, and glorifies it by transforming it into songs. The psalms are the reflections of David (and other men of God) primarily on the scriptures that preceded them. David is depicting himself in this psalm as an edenic tree, taking in the water and soil of God’s word, and turning it into sweet fruit — which we, as trees ourselves, can consume, and produce our own fruit in turn. Or, you might say, we take that fruit, and we transform and glorify it even further — for what does Paul say?

and be not drunk with wine, in which is disintegration, but be filled in the Spirit, speaking to yourselves in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody in your heart to the Lord, giving thanks always for all things, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, to the God and Father. (Eph 5:18–20)

In other words, don’t be consuming wine, which will cause you to lose your minds, but rather take the fruit of the law that David produced, and ferment it into the fire-water that is the mind of Christ. Once again, we see that scripture is surprisingly plain about how Christ dwells in us: we are truly filled with the Holy Spirit when we take in his word. The parallel passage to this is Colossians 3:16, where rather than telling us that we’re filled with the Spirit through psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, Paul says instead that the word of Christ will dwell in us richly. To have the word of Christ dwelling in us is thus functionally the same as being filled with the Spirit of Christ.

We consume Christ by consuming his word. He abides in us when we abide in his word.

Talking to ourselves

But what is the precise method that scripture gives for this?

It involves meditation, musing — but the Hebrew is literally “murmuring.” God is quite specific to Joshua that the word must be in his mouth, not merely in his eyes. This isn’t a case of simply reading the word, but speaking it to oneself.

This is quite counterintuitive to us. Modern people don’t read aloud to themselves. In fact, we’d feel dumb doing that. We’re afraid of sounding like idiots, because let’s be honest, if we heard someone else doing it, we’d be inclined to mock them.

Like, “What, are you still learning to read?”

But it’s worse than that too, because the word murmur here doesn’t just imply speaking aloud. It also implies musing. This is why it is translated meditate in most Bibles. There was a time when that was a pretty good translation; it is only quite recently that this changed, after Eastern religion was imported to the West through popular culture and the sexual revolution. If you consult Webster’s original dictionary, published in 1828, you will find that meditation meant:

To dwell on any thing in thought; to contemplate; to study; to turn or revolve any subject in the mind; appropriately but not exclusively used of pious contemplation, or a consideration of the great truths of religion.

Webster even cites Psalm 1:2 as his example of the usage.

If you consult a dictionary today, however, you will find that the accepted meaning has changed considerably — now it means:

To train, calm, or empty the mind, often by achieving an altered state, as by focusing on a single object, especially as a form of religious practice in Buddhism or Hinduism. (American Heritage Dictionary)

Now, this is still compatible with Christianity; the purpose of biblical meditation is to train the mind — though not through an altered state — by focusing on the single object of God’s revelation. But you see how the religious practice of Buddhism and Hinduism dominates the definition. Hence I don’t much like the translation of meditation these days, and prefer murmur — though it too leaves something to desired, because murmuring doesn’t really imply musing. If only there were a word that means, “to turn something over in the mind by speaking to yourself about it.” Perhaps someday there will be. Postmillennial English will no doubt reflect scripture much more accurately than 21st Century English. But alas, we make do with what we have.

All that to say, biblical meditation involves talking to yourself. It involves speaking the words of scripture out loud — not necessarily loudly, but out loud — and musing on them, also out loud. Drawing connections and conclusions. Asking yourself questions, and answering them. Saying to your soul, “Do you believe this? Believe it.” Or, “Do I do this? Do it.” Pondering aloud how you might go about reforming your life in light of what you have read. Repeating phrases that stand out to you, so that they may score themselves deeper into your heart, wearing the grooves of God’s mind into your own. If your heart was a vinyl record, it should start playing the scriptures if someone put it on a gramophone, because those are the vibrations it has had etched into it.

All of this is greatly facilitated by verbal speech. God made us to both remember things, and work out their meaning, more easily when we hear them spoken.

This is in fact such an important principle that God uses no fewer than three different words in Hebrew, to describe to us how we are to meditate or muse upon his word. He not only commands us in the model of Joshua to speak aloud to ourselves, but also very famously in Psalm 119 exhorts us repeatedly in the value of this exercise, using two other words:

In my heart I have hid thy saying,

That I sin not before Thee.

Blessed art thou, O Yahweh; teach me thy statutes.

With my lips I have recounted

the judgments of thy mouth.

In the way of thy testimonies I have joyed,

As over all wealth.

In thy precepts I meditate,

And I behold attentively thy paths.

In thy statutes I delight myself,

I do not forget thy word. (Ps 119:11–16)

The Hebrew word here translated meditate is different to the one used in Joshua 1 and Psalm 1 — but it, too, means to “converse (with oneself, and hence aloud)” (Strong). “In thy precepts I converse aloud with myself, and I behold attentively thy paths — in thy statues I delight myself; I do not forget thy word.” This is the manner in which the psalmist hides God’s sayings in his heart: by saying them. “With my lips I have recounted all the judgments of thy mouth.” It is expressly clear that this is a continual practice of speaking. Indeed, the same word is put in parallel with speech in verse 23:

Princes also sat — against me they spoke,

But thy servant doth meditate in thy statutes (Ps 119:23)

The comparison being drawn is between the speech of the princes and the speech of the psalmist — they speak against him, but he is safe because he converses aloud to himself in God’s statutes.

There is yet a third word that is used — for example in Psalm 119:97:

Oh how I have loved thy law!

All the day it is my meditation.

This time, the word translated meditation means to reflect or pray. And you might think, well, that can be done silently. We usually pray silently, don’t we? But once again, scripture furnishes us with plenty of information to know if that is normal. Think of what we learn when Eli witnesses Hannah praying at the tabernacle:

And it was, when she multiplied praying before Yahweh, that Eli was watching her mouth, and Hannah, she was speaking to her heart, only her lips were moving, and her voice was not heard, and Eli reckoned her to be drunken. (1 Sa 1:12–13)

Eli thought Hannah was drunk because she spoke silently to herself. This was not normal behavior — but she did not want to broadcast to the priests who were present all the private sorrow in her heart as she poured it out to God. She did not sin by praying silently, of course — but she did do something unusual. It was the normal practice of God’s people, as it has been throughout history until recent times, to speak aloud to God, as well as to themselves.

Now let us be frank. This is extremely awkward for modern people like us to do. It may even be mortifying to start with — because we are told that there is something shameful about talking to ourselves. Isn’t it supposed to be the first sign of madness? This is a cultural trope that you have probably never thought much about — but that is how the saying goes. “Talking to yourself is the first sign of madness.” Why? Why is it supposed to be insane to muse out loud to yourself? God doesn’t think it’s insane. Why do we have this ingrained into our culture? Doing the very thing God gave us as a primary tool for transforming our minds — is now a kind of casually diagnosed pathology.

I don’t want to read too much into it, like it’s a great conspiracy or something, but I do find it intriguing. It is certainly striking to compare how our culture thinks about this issue, and how God does. I think at best we can say that it reveals a surprisingly prideful attitude to the life of the mind, and I do wonder if there is some kind of connection to the pietistic or gnostic turn that the church took in the past few hundred years, where embodiment has been downplayed and even discounted as being of any importance. As if there’s something base or crude about having to speak the words of God to yourself out loud — and a truly pious, truly intelligent, truly spiritual person could do it inside their head, silently, purely in the mind, without need of bodily help.

But that is not how God made us. We should be speaking scriptures to ourselves out loud, and musing on them, turning them over not just in our minds but in our mouths. There is no question that God blesses such a thing, and offers great benefit from it, for he promises this to Joshua, and reiterates it in the psalms. “You need this,” he says in effect, “in order to surely hide my word in your heart, in order to surely walk in my ways, in order to surely have me with you — in order, surely, to be safe in this dangerous world that seeks to destroy you, and from the enticements of your own flesh: the sin that clings so closely.”

Singing to ourselves

But he does not just give us speech. When David muses and murmurs and converses aloud to himself in God’s law, he glorifies that law by transforming it into songs. Singing is beautified speaking. And in his wisdom, God has fittingly made us so that beautified speaking is even easier for us to remember than regular speaking. When David beautifies the law, he translates it, as it were, into a new format; a format that hooks even more readily into the heart, that stirs our affections even more directly. He elevates it. He makes the words into poetry, and then he adds glory to glory by setting the poetry to music.

This is also a format much more suited to public consumption — a way for us to share a meal of God’s word together. Hence Paul instructs the Ephesians and the Colossians, as we have seen, to speak and teach and admonish each other in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs. In singing psalms, we converse together in God’s words directly. In hymns and spiritual songs, we muse together upon them — for what are hymns and spiritual songs, if not reflections and ponderings upon the wondrous precepts and statutes and works and deeds of God (Ps 119:27), written down and set to music so that we may appreciate them together as a body?

Music not only amplifies the effect of God’s word upon our hearts; it even has a mysterious power that makes demons themselves tremble and flee. When we speak God’s word, our souls participate, so to speak, in the spiritual realities we are expressing. But when we sing God’s words — and our own musings upon them — it is more like our souls begin to resonate with the great truths we are giving voice to. Something is happening in the spiritual realm that we do not understand, but is used by David to drive the evil spirit from Saul (1 Sam 16), and is used by Jehosaphat to command even the hosts of God’s angelic army, as he has the Levitical choir lead the physical army into battle:

And when they began to sing and to praise, Yahweh set liers-in-wait against the sons of Ammon, Moab, and mount Seir, that were come against Judah; and they were smitten. For the sons of Ammon and Moab stood up against the inhabitants of mount Seir, utterly to slay and destroy them: and when they had made an end of the inhabitants of Seir, every one helped to destroy another. (2 Chr 20:22–23)

(Now in fairness, I am inferring that this was done through the work of angels, but I think I am on very safe ground given what scripture does reveal about the work of angelic armies that is taking place in the background. Think for instance of Elisha in 2 Kings 6, having the Syrian army struck blind after revealing to his servant that “they that are with us are more than they that are with them,” and opening his eyes to the horses and chariots of fire all around.)

In any case, singing has great power, and I want to encourage you to do it. Learn songs by heart. Spend time singing them to yourself, and to your family, and to each other at church. Participate enthusiastically whenever there is singing. Perhaps you are not a good singer — but I think we should be more ashamed of not singing, or singing reluctantly or quietly, than singing badly. “Make a joyful noise to the Lord,” the Psalmist says. By all means strive to improve, and practice will help you with that. But do not be ashamed to make a joyful noise, even if it is less tuneful than you would like.

I would only caution that you start with the psalms, since that is scripture’s own counsel. And when you sing hymns, consider both their musical and their lyrical form. How a song sounds means something. And what a song says can either follow scriptural patterns, or deviate from them. Will Drzycimski is doing excellent work in helping people think through this, over at Worship Reformation:

Reciprocal movement

Of course, in all of this, our minds must be engaged. It does no good whatever to speak or sing in God’s words, or muse over them, if all we are doing is mouthing sounds automatically. That is what the pagans do. The object is to fill the mind — not empty it.

But it can be easy to fall into a kind of mindless repetition when reading or singing. Let me therefore add to what I have said by observing a further pattern, starting with David’s words in Psalm 39:

My heart was hot within me;

While I was murmuring [musing/meditating] the fire burned:

Then spoke I with my tongue:

Yahweh, make me to know mine end,

And the measure of my days, what it is;

Let me know how frail I am. (Ps 39:3–4)

David meditates; then he prays. In other words, meditating in God’s word is only one half of the full process we should be engaged in.

We take in the word — but then we ourselves respond; or at least, it should be natural for us to do so.

The meditation produces prayer for David; this is the response that rises up naturally within him. The musings of his heart upon what he has taken in, move him to some new realization or concern, which then wants to come back out. God’s word always wants to return to him, but it does not return empty (Isa 55:11). We take it in, we fill it up, and we return it.

The man musing in God’s law is like a tree drawing up water in order to produce fruit. It is a two-step process. In and out again. Prayer — praise, thanksgiving, supplication — is the first of these fruits. You should be expecting this response within yourself. In a sense, it is spontaneous; it occurs naturally. But it must also be directed; it must be sought out, in order to take that raw response and refine it and draw it out further, to offer it up to God whole and complete and mature, rather than a stunted or unripe fruit. And this is a cyclical process, for the more we practice, and the more we are shaped by God’s own words, the better we become at forming our own words in the same way, to appropriately respond.

You will also find that this first fruit of prayer and praise breeds more fruits. The more you reflect on the word and respond to it with words of your own, the more your own heart and mind is shaped by them, and this cannot help but affect your whole life. It cannot help but issue in the kind of fruit we usually think about when we hear that word in scripture — good deeds, changed behavior, righteousness, piety. We see this movement in what Paul says to Timothy:

Till I come, give attendance to reading, to exhortation, to doctrine. Neglect not the gift that is in thee, which was given thee by prophecy, with the laying on of the hands of the presbytery. [Now, how is Timothy to ensure that he does not neglect this gift?] Meditate upon these things; give thyself wholly to them; that thy profiting may appear to all. (1 Tim 4:15)

Do you see the movement Paul is assuming? First Timothy must meditate, muse, ponder upon these things — then, he will give himself to them and his profiting will appear to all. The musing produces the fruit of a mature gift, practiced and perfect. There is a kind of cyclical action — in and out: “Meditate upon these things” — that’s in — “give thyself wholly to them” — that’s out. The movement occurs within Timothy first — in and out — but then, as it comes out of him, it moves into those around him, so that everyone sees it.

This movement, this in and out, is like breathing. God’s word goes in, but it doesn’t just stay in us; it returns back out again fuller than before, in the form of fruit. Not literal fruit, of course — but the word goes into us as something spiritual, something abstract — and then it comes back out of us as something embodied, something concrete. And this sets up a kind of cycle, where not only do we repeat this pattern, but others are caught up in it. In making the word concrete, embodying it, we are loving others. Timothy is called to love his flock by reading, exhorting, and teaching. This is faith working through love. And as he loves them, they in turn love him back. This is Timothy’s hospitality, and the same pattern plays out in all of us. We feed others — and they have a natural impulse, in response, that they should then feed us.

In marketing, this is called reciprocity. You give something, and so someone wants to give you something in return. But it works in marketing only because it is a creational principle built into the whole world — and especially into the nature of true religion. We are reciprocal creatures, and God himself is reciprocal. There is an eternal reciprocity within the Godhead. And that reciprocity is then expressed in God’s relationship with creation. And it is expressed in his word to us. This is God’s way of thinking: the eternal back-and-forth between the persons of God, and between God and creation.

Think on this: God calls; the earth exists. Or, if we move down a level to the image of God: the man calls a wife; she responds. He provides, she glorifies. He gives seed; she bears fruit. And of course, this pattern is repeated, not just in the relationship between God and the world, and man and woman, but also between Christ and his church. The head directs, the body acts. God speaks; we repeat his word back, with our own praise. Think of the continual call and response that takes place in worship itself:

Christ takes hold of us by calling us to worship;

We respond by blessing him in song.

Christ breaks us up and puts us back together through the preaching of his word;

We respond by giving offerings of prayer and praise.

Christ integrates us — and we integrate him, in the Lord’s Supper.

And then Christ commissions us;

And we respond by returning out to the world, to repeat this pattern on his behalf by calling others to repentance, so that they may respond in faith.

This pattern is so fundamental that you cannot escape it — though sadly many churches have done their best to adandon it in their liturgies. All of creation reflects it. Even stories are structured like this. There, and back again. The gospel is structured like this: Christ comes down, and Christ goes back up. The Holy Spirit convicts, and we repent. And the scriptures are structured like this. Have you noticed that most of the words we are given to sing or pray — the words most expressly fitted to our meditation — are arranged in parallels, in couplets:–

The fear of Yahweh is the beginning of wisdom…

And the knowledge of the Holy One is insight.

Give thanks to the Lord, for he is good…

His steadfast love endures forever!

Or think of the Lord’s prayer:

Call: Our Father, who art in heaven…

Response: Hallowed by thy name…

Call: Thy kingdom come…

Response: Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven…

Call: Give us this day our daily bread…

Response: And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors…

Call: And lead us not into temptation…

Response: But deliver us from the evil one.

I said before that meditation on God’s word is soul-forming. Well, I might not have used those exact words, but the whole idea is that meditation shapes our hearts to be more like God’s; it fills our minds with the mind of Christ. Most of the wisdom literature, the psalms and the proverbs, things we have written for us to sing and pray and murmur upon, are written in this reciprocal way — and I am convinced it is because God wants our hearts formed to naturally work in reciprocating movements: to call and expect a response; or to respond when we hear a call. And biblical meditation itself also follows the same reciprocal movement. It is in, and out; there, and back again. Meditate, pray. Muse, act.

Notable:

Given what I’ve said above, meditate on this…

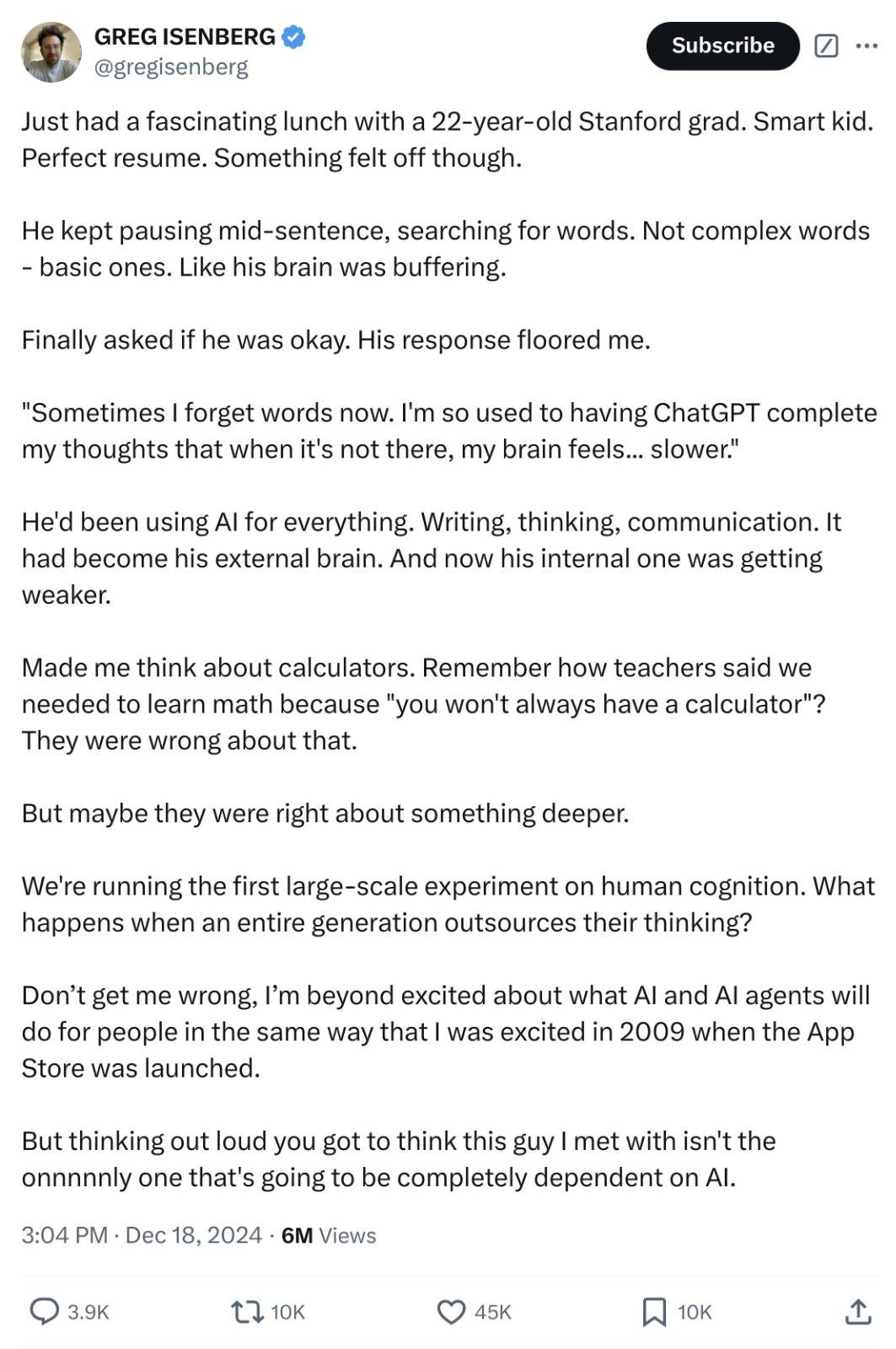

I found this tweet from the following video, where the money quote is:

…summarizing articles [with AI], while it sounds really helpful, is going to slowly burn out those active networks formed in your brain. You’ll find out down the road that you hate reading articles or books, and you just can’t focus anymore. You can’t follow the arguments, and you make it a habit just to have things summarized for you in the name of productivity and efficiency. But it’s really in the name of you not having the mental capacity anymore to think.

(What do you think happens when a large amount of the content you consume is only 280 characters, btw?)

See also:

Rainbows are fascinating:

Honey is a scam (shocked — shocked I say):

Joe Rigney was right:

Finally, Smokey and I are making slow but steady progress on putting out episodes explaining the biblical symbolism of clothing. Below is our most recent, and toughest episode — on head coverings. You’ll hear things in this which you won’t get from the engagement-farming popularizers…like why male priests in the Old Testament had to wear head coverings, but men in the New Testament don’t, while women do:

Until next month,

Bnonn